Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)

Origin

Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu has drawn much attention from the media in the past few years. Avian influenza originates from wild birds who are often unaware carriers of influenza A viral strains. Waterfowl in particular are thought to act as a reservoir of the virus and frequent testing has shown populations to nearly always be carriers of influenza viruses (although not always harmful strains). Symptomatically they are unaffected, however they are able to transmit this airborne virus to domesticated poultry such as chickens and ducks, birds which do not share the same immunity. Recently dogs have also been seen to be carriers of the virus. Economically this has a devastating impact as chickens may pass on the virus through saliva, secretions and excrement to other domesticated poultry, transmitted viruses remaining viable for 35 days in cold temperatures. In these circumstances the entire flock is often killed in order to prevent spread of the disease. Avian influenza viruses usually arise in two forms, one of a much higher pathogenicity than the other. Strikingly the more potent form has been seen to cause a rapid mortality rate in poultry of 90- 100 % within 48 hours. In addition three highly pathogenic avian strains H5N1, H9N2 and H7N7 have been reported to infect humans, therefore posing as a world wide health and agricultural threat.

Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu has drawn much attention from the media in the past few years. Avian influenza originates from wild birds who are often unaware carriers of influenza A viral strains. Waterfowl in particular are thought to act as a reservoir of the virus and frequent testing has shown populations to nearly always be carriers of influenza viruses (although not always harmful strains). Symptomatically they are unaffected, however they are able to transmit this airborne virus to domesticated poultry such as chickens and ducks, birds which do not share the same immunity. Recently dogs have also been seen to be carriers of the virus. Economically this has a devastating impact as chickens may pass on the virus through saliva, secretions and excrement to other domesticated poultry, transmitted viruses remaining viable for 35 days in cold temperatures. In these circumstances the entire flock is often killed in order to prevent spread of the disease. Avian influenza viruses usually arise in two forms, one of a much higher pathogenicity than the other. Strikingly the more potent form has been seen to cause a rapid mortality rate in poultry of 90- 100 % within 48 hours. In addition three highly pathogenic avian strains H5N1, H9N2 and H7N7 have been reported to infect humans, therefore posing as a world wide health and agricultural threat.

Image courtesy of https://www.flickr.com/photos/quiplash/56955463/ under a Creative Commons License.

Human infection

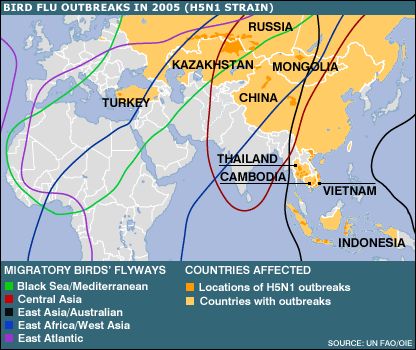

Bird migratory pathways are linked to the rapid worldwide transmission of avian influenza strains. Image courtesy of BBC News Online under a Creative Commons License https://www.flickr.com/photos/quiplash/52137112/

Symptoms

Symptoms may range from standard flu like symptoms such as cough, fever and rhinitis but have also been known to include eye infections, acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure due to severe internal haemorrhage leading to death. Mutation of the human influenza virus enables it to evolve mechanisms which exploit the host cell's immune response. For example proteases which originally inactivated the virus have been manipulated to conversely activate the virus. In humans the protease which mistakenly activates the influenza virus is located in the respiratory tract, hence influenza is a disease of the respiratory system. However proteases located in several organs are capable of activating the avian strain of the virus. This has severe implications for the pathogenic ability of the avian influenza virus which may therefore infect several organs in the body, perhaps explaining widespread symptoms in bird flu infected individuals. In addition the H5N1 strain is resistant to both amantadine and rimantadine, inhibitors of the M2 ion channel although neuraminidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir and zanamivir may be effective (see treatment and diagnosis).